VE Day 80: Our Family Stories

Over the past few weeks, we’ve invited colleagues to share their families’ stories from the Second World War.

It’s been a fascinating and moving process, something that feels uniquely ours amid a sea of more generic VE Day 80 commemoration content. This is an important moment – likely the last major anniversary where veterans will still be with us – and it deserves something meaningful.

These are our family stories, and we hope you find them as compelling, harrowing, and at times, truly extraordinary as we do. In writing them, we have attempted to remain respectful and honest throughout, avoiding embellishment whilst still evoking strong emotions. We hope that this allows you to connect with the real human experiences behind the history.

Aidan Fisher-Rowe – Associate Director (Fisher – Father’s Side)

Peter William Fisher – Aidan’s Great Uncle

Peter William Fisher initially served in North Africa and Italy before volunteering for the newly established Parachute Regiment, training at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire.

His first parachute jump took place from a converted Wellington bomber at RAF Ringway, near Manchester. During the exit, Peter struck his head (a mishap known as “ringing the bell”) and lost consciousness, regaining it just before landing. After this harrowing experience, he refused to jump ever again – a completely acceptable practice, of course, just as long as you’re not actually trying to become a paratrooper.

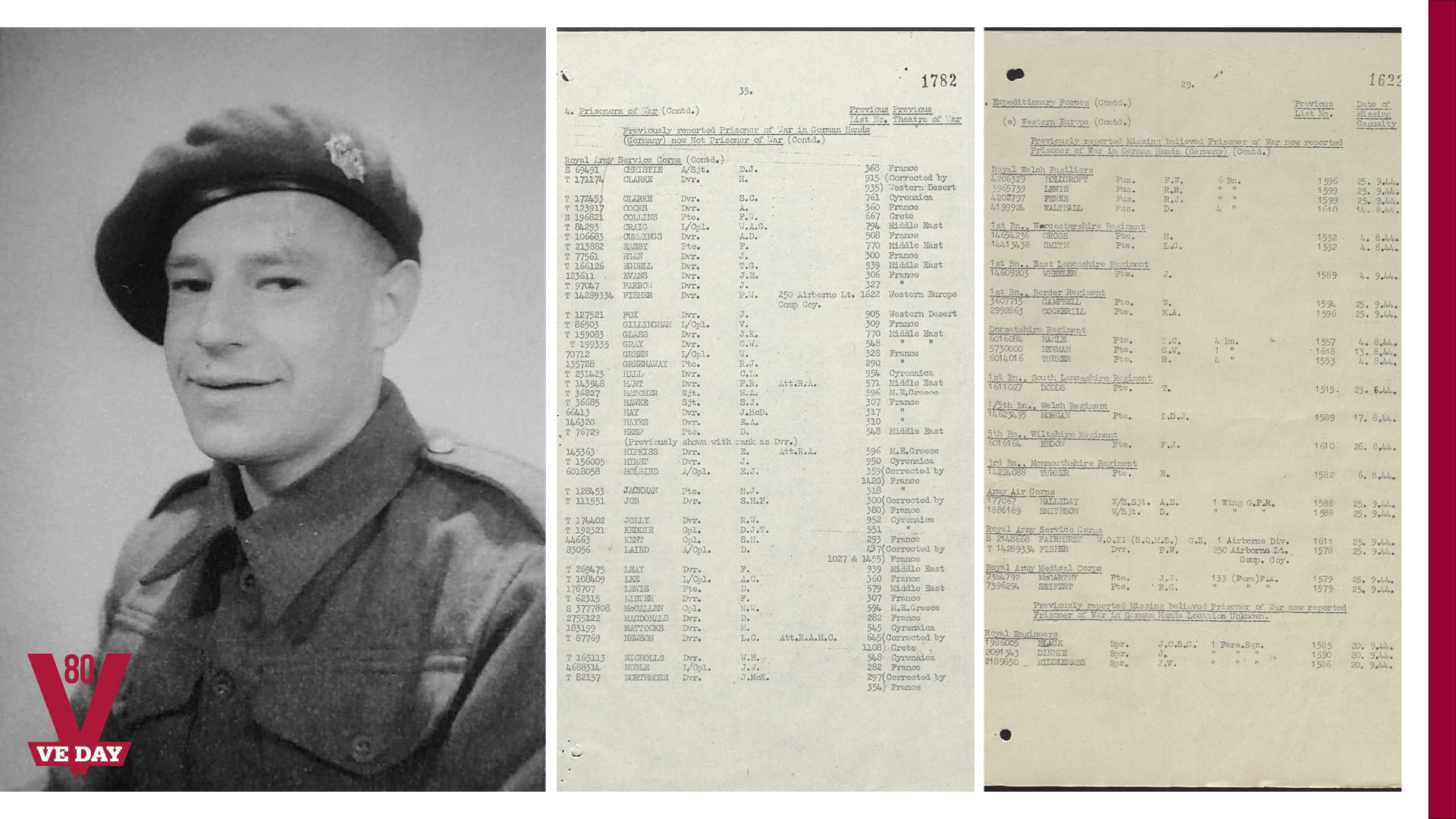

Despite his reluctance to throw himself out of a moving aircraft, Peter remained part of the 1st Airborne Division, joining the 250 (Airborne) Light Composite Company RASC as a Driver.

Between the 17th and 25th of September 1944, Peter took part in Operation Market Garden, landing at Arnhem by Horsas glider. At some point over the following few days, he was caught in an explosion that temporarily blinded him and led to his capture. In British Army casualty lists, Peter was initially reported as missing in October, before being confirmed as a Prisoner of War the following month (November).

Peter wasn’t alone, he was one of 400 British Paratroopers including Regimental Sergeant Major John Lord who were captured and imprisoned in Stalag XIB (11B / 357), Fallingbostel, Germany.

Eyewitness accounts tell us that when the 1st Airborne men arrived at the camp, they marched in as if on parade for the King. This incredible act of defiance amazed the German guards stationed there.

As a fit enlisted man below the rank of sergeant, Peter was, under the Geneva Convention, required to carry out ‘non-war work’ whilst in captivity. And although no official transfer records appear to exist, Fisher family legend holds that he was assigned to work as a coal miner in Poland, where he spent the final months of the war.

At some point between his capture and the end of the war, it is likely that Peter took part in one of the hundreds of forced marches across Poland and Germany. If he did, we would understand his silence on the matter.

Peter survived the war and, afterwards, trained as a teacher at Ebor College in York. He remained in the profession until his retirement, passing away whilst on holiday in Hunstanton on 4th June 1999.

In recognition of his service, Peter was awarded two medals: the War Medal 1939–1945 and the 1939-1945 Star.

Matthew Wellington (Lawes – Mother’s Side)

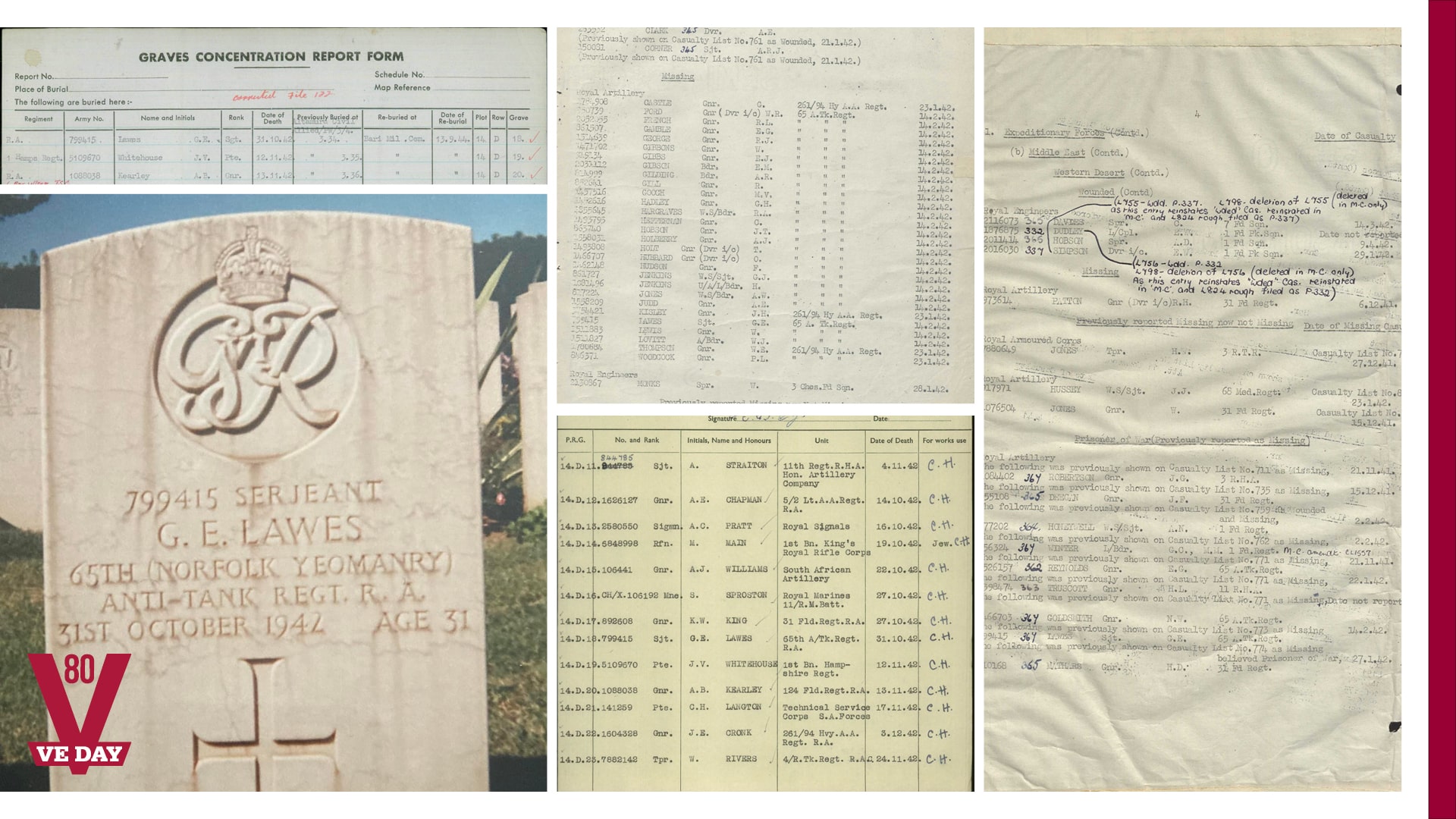

George Edward Lawes – Matthew’s Great Great Uncle

George Edward Lawes was a Serjeant in the 65th (The Norfolk Yeomanry) Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery.

He served with the British Expeditionary Force that landed in France in 1939, and was one of the 338,000 men that were miraculously evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940. As the war progressed, George was later deployed to the Western Desert campaign in North Africa.

Exactly what happened next is unclear. Recent research indicates George was reported missing on 14 February 1942 and later recorded as a prisoner of war about a month after. It’s possible he was captured during Erwin Rommel’s second offensive – or in the aftermath – when British forces were pushed back to the Gazala Line, just west of Tobruk. He was not alone: the same report lists 23 other men from his regiment as missing.

From that point forward, we can only presume George died in captivity. A Graves Concentration Report Form dated 22nd September 1944 notes that he was originally buried at the Altamura-Gravina Prisoner of War Camp in southern Italy.

As the largest Prisoner of War camp in the country, it was described by those held there as “Hell on Earth.” Food rations were inadequate, the camp was overcrowded and unsanitary, and despite the huts being made of stone, conditions were damp and muddy. Built near a swamp, the camp was plagued by malaria, making daily life even more unbearable. The report lists George’s date of death as 31st of October 1942 – we can only assume due to the appalling living conditions.

Following the Allied landings in Sicily, the camp was abandoned and officially closed by July 1943. Just over a year later, on 13 September 1944, George was reburied with honour in the Bari War Cemetery, where he now rests, under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Vicky Luck (Roome – Mother’s Side)

Arthur Roome – Vicky’s Grandad

Arthur joined the Royal Air Force at the outbreak of the Second World War. Upon learning he was to be stationed in Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa, he married his sweetheart in a whirlwind ceremony in Derby, England.

Though Sierra Leone saw no large-scale battles, the colony played a vital role in the Allied war effort. Freetown served as a key convoy station, providing a crucial stopover for ships crossing the Atlantic. Several RAF squadrons were based there, including those operating the famous Catalina and Sunderland seaplanes. These aircraft could land on water and were responsible for patrolling vast stretches of ocean and hunting down German U-boats in both the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

After the war, Arthur returned home with various bits and bobs collected during his time overseas. This assortment of items included a handbag he gifted to his daughter (Vicky’s mum) many years later. When she asked what he’d done during the war, his reply was swift and to the point: “Not a lot.” To this day, we’re not entirely sure what Arthur got up to. Like many servicemen of his generation, he wasn’t inclined to share the details. Perhaps he really did have a quiet war. We’ll likely never know for certain.

He possibly felt that he had a lot to live up to, living somewhat in the shadow of his father-in-law, Herbert Alfred Disney, a decorated First World War veteran. Family legend holds that one of Herbert’s medals for gallantry was awarded by George V himself. During the Second World War, Herbert continued to serve the nation, this time in the Home Guard or as many refer to them, “Dad’s Army”.

Claire Seymour (Seymour – Father’s Side)

George Ernest Seymour – Claire’s Grandad

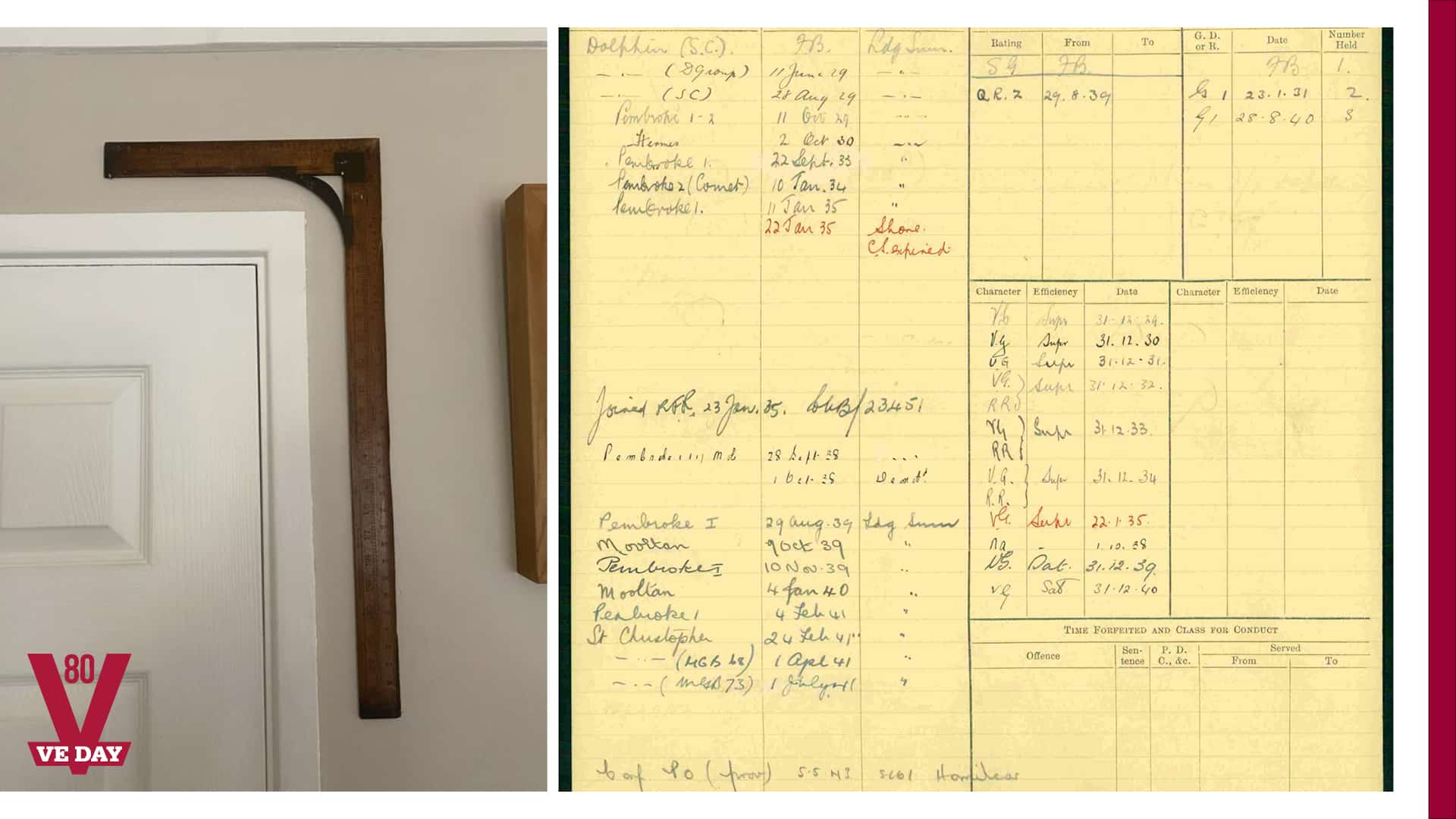

George was born in Balham, London, in January 1905. His post-war discharge papers show that in 1929, at the age of 24, he joined the Royal Navy as a Tailor’s Assistant and was based at HMS Dolphin, the home of the Submarine Service. As a Tailor’s Assistant, he would have worked alongside a Master Tailor, assisting with tasks like taking measurements, preparing materials, and choosing fabrics. The work likely included making uniforms and repairing clothing – a role that suggests he had prior experience in tailoring as a civilian.

In 1932, he appears to have joined the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR), indicated by the ‘RR’ or ‘Rating Reserve’ acronym under his character review. The RNR would have allowed George to maintain his civilian career whilst still contributing to the Royal Navy’s operational capabilities.

He then spent the following years moving between various coastal ports and naval facilities, before joining the Royal Fleet Reserve (RFR) in January 1935.

When war broke out in September 1939, George appears to have been onboard HMS Mooltan, a former P&O liner built by Harland & Wolff (of Titanic fame) and retrofitted to serve as an armed merchant cruiser attached to the South Atlantic Station. The South Atlantic Station had bases at Freetown, Sierra Leone, and Simonstown, South Africa.

In November 1939, he returned to London and the barracks at Chatham, known as HMS Pembroke, before once again setting off on the Mooltan around January 1940.

A year later, in early February 1941, he is recorded as serving once again at HMS Pembroke, before joining HMS St Christopher at the end of that month. HMS St Christopher was a Coastal Forces training base located in and around Fort William, Scotland. The base had a staff of several hundred, billeted in hotels around the town, with extra space provided by Nissen huts.

The records we’ve found stop at this point – leaving a rather large information gap between 1942-45 – before showing George as released in Class A on 17 October 1945, once again at HMS Pembroke.

The discharge papers show that George was regularly commended for good conduct and was often scored as Supr (Superior) and VG (Very Good) for efficiency. Seymour family legend holds that George once worked on a custom-made suit for Prince Rainier III of Monaco, who joined the Free French Army in 1944, serving as a Second Lieutenant. This tale may in fact be true, as it is well recorded that the Prince wore his own custom military uniform throughout the war – based on the uniforms Napoleon Bonaparte had worn.

Claire still has her grandfather’s measuring tool, mounted on a wall in her home in Norwich.